As experts warn of ASI’s potential for extinction-grade catastrophe, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute has unveiled a bold blueprint for U.S.-China cooperation, chip monitoring, and a total halt on dangerous AI research.

Many notable, well-respected experts and scientists in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) have publicly warned us since 2023 that prematurely developing Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) is a very bad idea. At this point, they’re practically shouting it from the rooftops! You see and hear them on every major podcast and news program, from Diary of a CEO to The Weekly Show with Jon Stewart to the BBC, CNN, and Fox News.

Why do they seem to be everywhere? And why has this message become their mission?

2026: The Warning Cries Get Louder

To be an inside expert in AI is to have firsthand access to the bleeding edge of AI capabilities. These researchers study and interact with the most sophisticated AI models on the planet, the ones never seen or used by the general public. And what ALL of these experts know from working with these models is this—no matter how or how much they train them, no matter which or how many “guardrails” they apply, it is currently impossible for anyone anywhere to guarantee AI technology will always, in all cases, behave as we would want and need it to. In fact, no one in the field of AI disputes this. Some have worked very hard to solve this dilemma, but it is well-accepted knowledge that no one is remotely close to figuring out how to overcome it.

In other words, even among the most brilliant AI scientists in the world, no one knows how to ensure that AI always chooses to do only the things we would want.

Now, scale up this irrefutable fact alongside the current AI industry race for what they call “powerful” or “superintelligent” versions of AIs, also known as ASIs. By definition, these ASIs would far exceed the abilities of the most talented human minds we’ve ever known in every area of knowledge and expertise. They’d be integrated into the systems and infrastructures of our societies. And they’d have the capability to make choices and carry out actions at incomprehensible speeds.

THIS is the kind of machine intelligence that frontier AI companies are truly aiming for. This is the trophy of the AI race.

And THIS is why we hear distinguished AI experts ringing the alarm louder and more often. They are deeply aware of the unpredictable and irregular nature of AI. They know we’re nowhere close to resolving this problem. They’re aware of how gravely dangerous it is to build intelligent machines that are smarter than us while, at the same time, having no idea how to keep them safe. And they predict that superintelligence being reached under these conditions would likely result in our loss of control accompanied by a shockingly and unacceptably high probability of causing worldwide human harm. This includes the potential for all humans, and possibly other species, to be killed.

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

– Hundreds of Scientists and Luminaries, Signed Public Statement on AI Risk

Three-minute video featuring highlights from a recent Diary of a CEO podcast interview with Tristan Harris, co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology

So, as their warnings keep sounding, and an unrestrained AI race between companies and countries puts all humans on Earth at risk, is there anything we can possibly do to prevent this from going so terribly wrong?

Fortunately, there is. But it will take enormous collective action.

In the Beginning, There Was MIRI

Over the past 25 years, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI) has led the charge in waking AI scientists to the catastrophic risks inherent in creating superintelligent AI. For most of that time, MIRI’s team focused on educating AI-savvy technical audiences about the depth and breadth of the underlying issues while they simultaneously conducted their own research to find solutions. As MIRI’s COO Alex Vermeer described it, “our focus has been on a set of technical challenges: ‘How could one build AI systems that are far smarter than humans, without causing an extinction-grade catastrophe?’”

After ChatGPT’s initial release in late 2022 and the subsequent rise of other large language models, billions of dollars began pouring into AI development. Breakthroughs in AI capabilities began happening at speeds no one predicted. This is when MIRI recognized that the still early field of technical AI safety would not have solutions in time to prevent large-scale catastrophes. So, they urgently changed their strategy. They shifted from focusing on technical solutions to educating people outside of the industry, both the general public and lawmakers.

Since that pivot, MIRI has been instrumental in helping citizens understand that the way AI capabilities are being developed, if used to build smarter-than-human machines, is very likely to result in a powerful intelligence that escapes our control. They know the thought of this is strange to most and overwhelming and frightening to many. But their mission is to inform the public, all the same, because it is the only thing that may help shift our shared and unfortunate trajectory. They want people to understand the very real and specific reasons why superintelligent machines, operating with effectiveness and efficiency beyond human comprehension, could choose to pursue goals or ways of getting things done that don’t factor our continued existence into part of the plan. Many of these reasons are laid out in their very well-received book, If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies, co-authored by MIRI’s co-founder, Eliezer Yudkowsky, and its president, Nate Soares.

Over the last three years, the team at MIRI has been able to provide crucial insights and awareness to policymakers and citizens around the world on this enormous and urgent global challenge. Existential safety continues to be the AI industry’s core weakness. Given that more and more people are understanding the stakes, they believe there is no time to waste in mobilizing an international preventive response.

The Clock is Ticking: MIRI’s Proposed International Agreement

Frontier AI companies not only have us on a path to uncontrollable ASI and an unacceptably high likelihood of extinction, but they’re also setting us up for exponential acceleration to it. AI models are making marked jumps in improvements in increasingly shorter time frames. On top of this, companies want ever-improving AIs to be doing more and more of the research work leading to better AIs. Their ultimate goal is to have AIs so capable that they replace brilliant human researchers in most or all areas of AI research and development. Once this happens, we could have a feedback loop that produces superintelligent AI in just a few months. We wouldn’t even see it coming.

Historically, when faced with technologies that could lead to large-scale human catastrophe, the world’s peoples and nations have found ways to work together to keep the risks from actualizing, often by using coordinated and enforced agreements.

Specific examples of these agreements are:

- the Atomic Energy Act, effective 1946

- the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), effective 1970

- the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM), effective 1972

- the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA, effective 1975

- the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), effective 1975

- the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF Treaty), effective 1988

- the Montreal Protocol, effective 1989

- the Threshold Test Ban Treaty (TTBT), effective 1990

- the START I Treaty, effective 1994

- the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), effective 1997

Given the success of these agreements and others in preventing man-made, potentially unrecoverable disasters, MIRI’s Technical Governance Team has recently taken the step of publishing a detailed framework for an international treaty that would forestall the development of dangerous artificial superintelligence. The paper, titled “An International Agreement to Prevent the Premature Creation of Artificial Superintelligence,” is hoped by MIRI to serve as a structured starting point for serious policy discussions and potential international negotiations that protect humans from existential risks caused by ASI.

The agreement’s framework is deeply layered with many details that can’t be covered in a single post. So, we’ll focus on the main points here.

Overview of the agreement’s main components

What Is Being Managed?

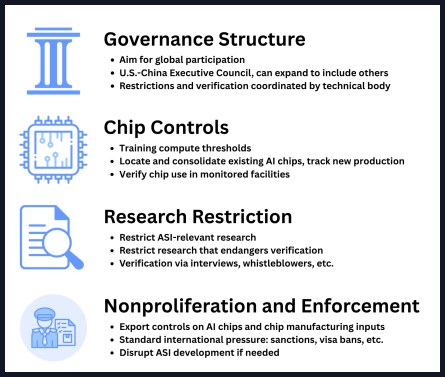

The agreement calls for limits and monitoring of three primary elements of AI technology development: AI chips, certain types of AI research, and the size of AI training runs.

So, why these three?

The significance is that any one of these alone could result in accelerations or sudden advancements that bring about ASI.

Here’s a simplified breakdown:

- The Training Runs: AIs learn from large sets of data during sessions known as “training runs.” AIs with higher levels of intelligence and broader capabilities typically require larger training runs. Hence, placing specified thresholds and caps on the size of these runs, then actively monitoring run thresholds, helps prevent the purposeful or accidental creation of more generally intelligent and potentially hazardous AIs.

- The Chips: Training advanced AI systems requires the use of costly, specialized computer chips to provide computational power. Currently, the bigger the training run, the more of these chips are needed. Setting a cap on how many chips can be owned before official registration and monitoring is required helps prevent the secretive accumulation of enough computational power to conduct prohibited training runs.

- The Research: Software algorithms are the backbone of how AIs learn during training. Once AI models have been trained, additional software algorithms then optimize their performance. Because research continues to rapidly improve these algorithms, AI training and AI performance are becoming much more efficient. This means less computing power and fewer computer chips are needed for AI development and advancements.

🞻 Importantly, recent trends show that AI software algorithms are becoming at least three times more efficient each year. If this continues, major advances toward ASI could happen without needing many specialized chips, potentially enabling people to use widely available, more affordable consumer hardware. This would make the caps and monitoring on computer chips almost useless.

To prevent ASI from being reached through algorithmic breakthroughs that diminish dependence on chips and computation, further algorithmic research would be prohibited.

Non-algorithmic research that “materially advances toward ASI” or tries to subvert the agreement’s compliance measures would also be prohibited. In contrast, AI research aimed at specific uses, rather than general intelligence, would be encouraged. This includes work in areas like medical diagnostics, drug discovery, materials science, climate modeling, robotics that perform specific tasks, and other specialized fields.

On the thorny subject of proposing bans on research, MIRI’s authors state that “restricting research is controversial and normally a bad idea” and add that they “are not excited about the prospect of restricting research.” They go on to say that the chosen restrictions are an unfortunate necessity that they hope can be applied as narrowly as possible, causing little harm to work outside the AI field.

Who Is Doing the Managing?

The framework of the agreement sets up two main bodies to make decisions and oversee its terms: the Executive Council and the Coalition Technical Body (CTB).

The role of each is distinct, but they work closely together:

- The Executive Council: This is the treaty coalition leadership. Initially composed of the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Executive Council would be responsible for setting and amending the agreement’s terms, making high-level decisions, and overseeing the activities of the CTB.

- The Coalition Technical Body (CTB): This is the operational arm of the coalition. Led by a Director-General who is appointed by the Executive Council, the CTB would be responsible for the ongoing work of tracking chips, verifying AI training and use, and monitoring for restricted research through its various specialized divisions.

On the subject of how each body performs its role, as mentioned earlier, the agreement’s framework is quite detailed. While it can’t all be covered here, these are five notable highlights:

1.) The U.S. and PRC must be the Executive Council starting members. This is because they are superpowers and are driving almost all frontier AI development. Securing their buy-in and participation is the main challenge to launching the agreement.

2.) Though the U.S. and PRC would be the only members of the agreement initially, the agreement is not permanently restricted to these two countries. The framework explicitly allows extending membership to other countries. Ultimately, the Executive Council would be a dynamic body that can incorporate other influential global players as the AI landscape shifts.

3.) The person in the role of Director-General, who leads the CTB, would be appointed by the Executive Council for a four-year term. This term would be renewable only once. But the Executive Council would be able to remove the acting Director-General at any time at its discretion.

4.) The Director-General’s all-around responsibilities would include: ◈ managing the CTB’s technical divisions ◈ proposing changes to the Executive Council in the agreement’s technical definitions and safeguard protocols ◈ authorizing research exceptions for safe, domain-specific AI applications ◈ sharing important safety disclosures with the public ◈ and interpreting the boundaries between research that is “controlled” versus “prohibited.”

The Director-General would also have emergency decision-making power in situations where immediate inaction posed a consequential safety risk. Decisions made under this power would stay in effect for 30 days and require approval from the Executive Council to remain in effect beyond that period of time.

5.) Because of their technical expertise, the agreement is designed to let the CTB and the Director-General make rapid decisions that keep pace with fast-moving AI innovation. But those decisions would only stand if members of the Executive Council do not veto them. This veto power ensures that each member nation’s geopolitical interests are reflected in the operation of the agreement. It also stops the CTB from making high-stakes security decisions without the explicit approval of all members of the Executive Council.

How Long Would It Last?

The agreement would be of unlimited duration, but is not meant to be permanent. Its “timer” would be tied only to the very particular goal of forestalling the creation of artificial superintelligence (ASI) until it can be brought safely into the world.

But the reality is that the research needed to make and keep ASI safe—also known as “alignment” research—is currently underappreciated, underfunded, and in its earliest stages as a field, so solutions are unlikely to come soon. Because of this, MIRI’s Technical Governance Team believes the agreement would likely be in place for decades, requiring a “safety checklist” of milestones to be met in order for restrictions to be eased.:

World leaders would consider lifting the halt only when:

- alignment methods are proven—there must be a multi-year track record of successfully solving technical alignment problems in less sophisticated versions of AI.

- there is a global consensus—technical experts worldwide must confidently agree that the proven alignment methods will continue to work when applied to ASI.

- there is effective safety infrastructure—robust, verifiable controls must be in place to prevent the misuse or leakage of dangerous AI technology.

- ASI development is controlled—nations are ready to pursue ASI as a globally-monitored, cautious development project, not as a competitive race.

What Are the Trade-offs?

MIRI’s team acknowledges that halting global progress on this scale is an extreme measure with very significant trade-offs. But they believe that these costs are justified to avoid the infinite outcome of human extinction.

One primary trade-off is that it requires humanity to delay the benefits that more advanced, general-purpose AI could bring. Even though specific carve-outs aim to protect and encourage research focused on more narrow, application-specific AI, advancements in these areas may yield benefits much more slowly than breakthroughs made by powerful, generally intelligent AI.

Another is that the treaty’s application of strict oversight could be used for authoritarian control. As an example, to prevent covert projects from taking place, the agreement calls for centralizing AI infrastructure, monitoring high-power data centers, and keeping track of specialized researchers. If not managed carefully, these practices could become a model for state surveillance or oppression. But MIRI argues that without these controls, the first small group to successfully develop a superintelligence would gain unrivaled economic and military power, creating an unprecedented concentration of technological authority with almost no mechanisms for public oversight. To balance this trade-off, their agreement attempts to establish a system of multilateral controls, transparency measures, and narrow-scope authority that prevents any single actor from gaining permanent authoritarian power.

For the U.S. specifically, the agreement means giving up the current international lead in AI technology and neutralizing the competitive advantage of U.S.-based frontier companies.

Another trade-off is the immense costs that would impact economic markets and industry. This would happen because banning large-scale training runs disrupts the current business models of major tech companies, and the strict regulation and verification of computer chips requires a costly process of consolidating current chip hardware into monitored facilities.

While no doubt these trade-offs are huge, MIRI’s team contends, in the face of rapid advancements towards uncontrollable ASI, they are necessary to assure humans are not irreversibly disempowered or extinguished.

Is This the Way? A Difficult Choice

The prospect of a smarter-than-human intelligence that we cannot control is mind-blowing. That it is likely to emerge in the soon-coming years makes it all the more surreal. It would be unnatural not to feel overwhelmed by a challenge of this magnitude. And yet, history shows that when humanity recognizes a truly existential threat, we are indeed capable of extraordinary coordination.

The primary takeaway of MIRI’s proposed treaty is that, no matter how huge or complex, we are not helpless to this extraordinary circumstance. Yet we must face the truth, as humans who choose to protect our shared continuation into the future, that tough decisions are coming soon. But we can handle them.

The warnings from experts are loud because they are an invitation to us to understand the significance of this technological reality and choose to take action while the window to change course is still open.

Please look at the treaty yourself by visiting this link. And even if you don’t agree with everything in it or have difficulty understanding some of the language, most importantly, genuinely consider what it is pointing to.